Motivation & Overview

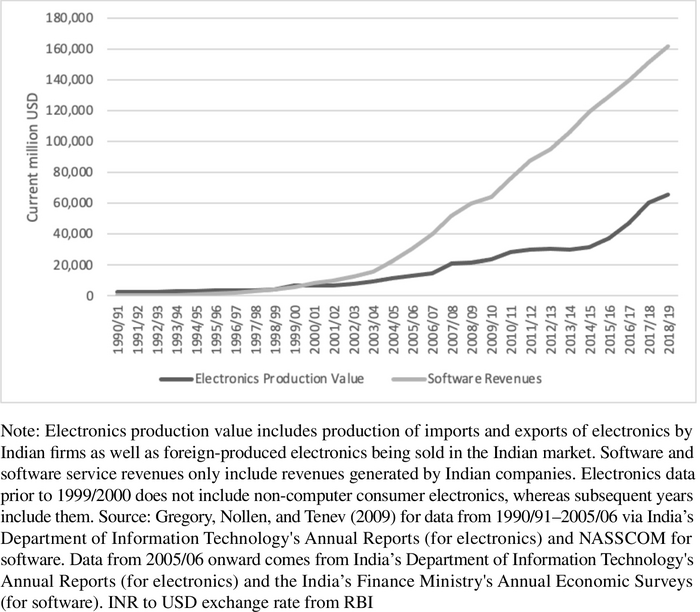

India’s services sector is internationally renowned and has helped propel the country’s economic growth. Indeed, in recent years, a majority of the value added to India’s GDP has been concentrated in services. Especially noteworthy are India’s software and computing services, which include large multinational conglomerates like Infosys and Tata Communications Services.

Yet as Indian software has flourished, the growth of its computer hardware and manufacturing has been sluggish. Tellingly, India is still a net importer of hardware and other electronics. At first glance, this divergence is puzzling because both the software and hardware sectors should have benefited from India’s educated labor pool and infrastructure. How can these different sectoral outcomes be explained?

Fig. 1: Electronics production value compared to software and software service revenues.

In “Comparing Advantages in India’s Computer Hardware and Software Sectors,” Dinsha Mistree and Rehana Mohammed offer an explanation in terms of state capacity to meet the different functional needs of each sector. Their account of India’s computing history emphasizes the inability of various state ministries and agencies to agree on policies that would benefit the hardware sector, such as tariffs. Meanwhile, cumbersome rulemaking procedures inherited from British colonialism impeded the state’s flexibility. Although this disadvantaged India’s hardware sector, its software sector needed comparatively less from the state, building instead on international networks and the efforts of individual agencies.

The authors provide a historically and theoretically rich account of the political forces shaping India’s economic rise. The paper not only compares distinct moments in Indian history but also draws parallels with other landmark cases, like South Korea’s 1980s industrial surge. Such a sector-based analysis could be fruitfully applied to understand why different industries succeed or lag in emerging economies.

Different Sectors, Different Needs

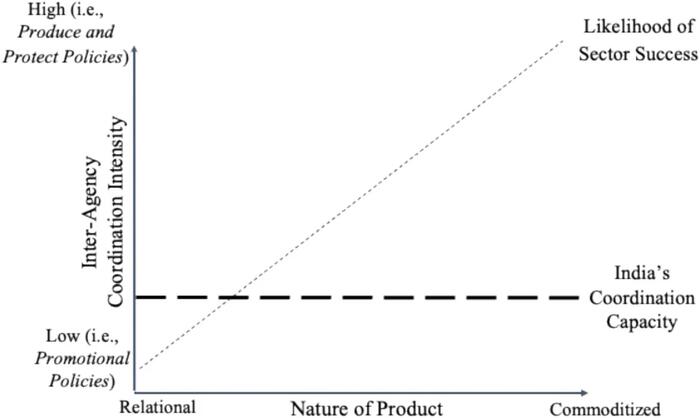

In order to become competitive — both domestically and (especially) internationally — hardware manufacturers often need much from the state, what the authors call a “produce and protect regime.” This can include the construction of factories and the formation of state-owned industries (SOEs), as well as tariffs to reduce competition or labor laws that restrict union strikes. Perhaps most importantly, manufacturers need a state whose legislators and bureaucrats can coordinate with each other in response to market challenges. Such a regime is incompatible with excessive “red tape” or with the “capture” of regulators by narrow interest groups. Because customers tend to view manufactured goods as “substitutable” with each other, firms will face intense competition as regards price and quality.

Fig. 2: Inter-agency coordination required for sectoral success.

The situation is very different for service providers, whose success depends on building strong relationships with customers. States are not essential to this process, even if their promotional efforts can be helpful. Coordination across government agencies is similarly less important, as just one agency could provide tax breaks or host promotional events that benefit service providers. Compared with manufacturing, customers tend to view services as less substitutable — they are more intangible and customizable, which renders competition less fierce. Understanding India’s computing history reveals that the state’s inability to meet hardware manufacturers’ needs severely constrained the sector’s growth.

The History of Indian Computing

Although India inherited a convoluted bureaucracy from the British Raj, the future of its computing industry in the 1960s seemed promising: political elites in New Delhi supported a produce-and-protect regime, relevant agencies and SOEs were created, and foreign computing firms like IBM successfully operated in the country.

Yet by the 1970s, some bureaucrats and union leaders feared that automation would threaten the federal government’s functioning and India’s employment levels, respectively. Strict controls in both the public and private sectors were thus adopted, for example, requiring trade unions — which took a strong anti-computer stance — to approve the introduction of computers in specific industries. The authors make special mention of India’s semiconductor industry. It arguably failed to develop due to lackluster government investment, the need for manufacturers to obtain multiple permits across agencies, decision makers ignoring recommendations from specialized panels, and so on.

Meanwhile, implementing protectionist policies proved challenging. For example, decisions to allow the importation of previously banned components required permission from multiple ministries and agencies. After India’s 1970s balance-of-payments crisis, international companies deemed inessential were forced to dilute their equity to 40% and take on an Indian partner. IBM then left the Indian market. At the same time, SOEs faced growing competition over government contracts and workers, owing to the growth of state-level SOEs.

The mid-1980s represented a partial turning point as Rajiv Gandhi became Prime Minister and liberalized the computing industry. Within weeks, Rajiv introduced a host of new policies and shifted the government’s focus from supporting public sector production to promoting private firms, which would no longer face manufacturing limits and would be eligible for duty exemptions. Changes to tariff rates and import limits would not require approval from multiple agencies. Meanwhile, international firms reengaged with Indian markets via the building of satellite links, facilitating cross-continental work, such as between Citibank employees in Mumbai and Santa Cruz.

However, this liberalizing period was undermined and partially reversed after 1989, when Rajiv’s Congress Party (INC) lost its legislative majority and public policy became considerably more fragmented. Anti-computerization forces, especially the powerful Indian trade unions, worked to stymie Rajiv’s reforms. Pro-market reformists were forced out of their positions in Indian bureaucracies. Rajiv was assassinated in 1991, after which Congress formed a minority government with computer advocate P. V. Narasimha Rao as PM. Yet all of this occurred at a delicate time, as India was at risk of defaulting and had almost completely exhausted its foreign exchange.

By the late 1990s, both the hardware and software sectors should have benefited from the rising global demand for computers, yet India’s history of poor state coordination hindered manufacturers. Meanwhile, software firms were able to take advantage of global opportunities given their comparatively limited needs from state actors and political networks — for example, helping European Union banks change their computer systems to Euros. Ultimately, the Indian state has powerfully shaped the fortunes of these different sectors.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.