Motivation

Political parties have long reflected dividing lines between groups in a society, often called political ‘cleavages’. Examples include workers vs. business owners, Protestants vs. Catholics, and urban vs. rural constituents. Civil society organizations (CSOs) — such as unions, churches, and chambers of commerce — have historically shaped the content and strength of these cleavages.

However, both CSOs and cleavages have changed in recent decades. For one, traditional cleavages have declined in importance, and new divides have emerged, such as between the so-called winners and losers of globalization or between those on one side or the other of the culture wars. In addition, formal CSOs have seen declining membership and reduced political influence, while informal groups and more episodic activism have grown. While CSOs and political parties used to have highly formalized relationships, they now tend to engage with each other more opportunistically and sometimes antagonistically. It seems clear that CSOs continue to influence political cleavages — both old and new — in the 21st century. But how exactly does this occur?

Contribution

In “Cleavage Theory Meets Civil Society,” Alex Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Endre Borbáth, and Swen Hutter examine the varied historical and contemporary relationships between CSOs, cleavages, and political parties in Western Europe. The authors develop a general framework for understanding the relationship between CSOs and cleavage development, providing insights into how contemporary politics reflects long-term changes in the structure of civil society.

The paper is set against social science research on cleavages, which can be divided into two broad streams. First, classical scholarship emphasized the importance of early 20th-century mass associations, such as unions, in shaping cleavages and party politics. By contrast, newer work, written against the backdrop of a changing CSO landscape, has viewed CSOs as largely irrelevant, arguing that opposition parties shape cleavages via direct interactions with voters. Neither body of previous work provides a compelling framework for understanding how contemporary CSOs — given their fragmentation, informationalization, and politicization -- matter for cleavages.

The authors also shed light on the phenomenon of polarization, which is a key part of democratic backsliding. Indeed, electorates are polarized around several cleavages — economic, religious, and cultural — that populist leaders have used to justify excluding their opponents from politics, portraying them as existential threats to a specific way of life.

Processes and Mechanisms

The authors suggest that cleavage development can be seen as the culmination of three processes, which CSOs may influence in key ways. The first is “group formation,” which concerns how individuals come to identify as workers, congregants, or otherwise. The second process is “political institutionalization,” which entails cleavages being embodied in party competition. The third is “political stabilization,” whereby cleavages are reinforced over time by parties.

| Stage of cleavage development | Importance of political linkage | Importance of social closure |

| I. Group formation | Low | High |

| II. Political institutionalisation | High | Medium |

| III. Electoral stabilisation | High | High |

Table 1. Role of civil society across stages of cleavage development.

To understand how CSOs might shape these three processes, the authors outline two mechanisms. The first is “linkage,” whereby CSOs communicate group demands and pressure political parties to represent them. Linkage is hypothesized to be more important during the latter processes of institutionalization and stabilization; it was historically important in group formation but less so today because of the aforementioned decline of formal CSOs.

The second mechanism is “social closure,” which concerns how group boundaries are solidified. CSOs are hypothesized to contribute to social closure by bringing group members together and organizing them around shared demands, increasing their sense of ingroup identification. This mechanism is important for group formation as well as political stabilization.

CSOs still appear to facilitate linkage and social closure, albeit in different ways than in the early 20th century. For example, CSOs are less likely to have formal links to parties but continue to exert pressure by organizing around individual issues, candidates, and elections. Voters’ relationships to CSOs are also more varied, creating divisions within the electorate between highly-active individuals who have a strong sense of group identity and people who are less ‘anchored’ to the cleavage. The authors also hypothesize that some of these dynamics may produce asymmetric changes across the left and right, as the strength and tactics of CSOs vary.

| Trend in civil society | Implications for political linkage | Implications for social closure |

| Fragmentation | Civil society groups have less capacity to present unified demands to parties and are more likely to compete for influence and adherents. Groups that persist are likely to be highly mobilised and ideologically distinct, exerting targeted pressure on priority issues and succeeding when they find points of cross-organisational consensus. | Groups and identities likely to be more heterogeneous; individuals tend to form multiple, competing group attachments which vary over time in their personal salience. Likely to produce pockets of high social closure amongst ‘untethered’ masses. |

| Informalization | Civil society organisations less likely to have ongoing formal relationships with parties; influence comes through mobilisation in moments of political crisis or indecision. | Interactions between group members become less frequent and more spontaneous, reducing social closure for most people while increasing it amongst committed adherents. |

| Politicisation | Landscape of civil society organisations is more differentiated and issue-specific, with groups pursuing alternate (and occasionally competing) linkage strategies; pressure on parties comes from different sources during different periods of mobilisation and is most effective in moments of coordination. | Salience of voters’ group identities changes across different moments, depending on how parties and civil society groups invoke them. ‘Groupishness’ of the population as a whole may become very high in particular critical moments. |

| Overall effect | Move towards more volatile forms of linkage, operating through punctuated equilibrium moments of mobilisation and contestation rather than stable formal ties. | Proliferation of multiple identities leads social closure to bifurcate; ‘tight’, mobilised groups coexist alongside heterogeneous masses who become sporadically activated. |

| | Combination of the three trends widens the number and types of civil society actors that intervene in processes of political linkage, leading different groups to exert influence at different times and ‘successful’ pressure to hinge on effective cross-group coordination. | Combination of the three trends simultaneously widens and blurs possibilities for participation, leading to a growing gap between people who are activated consistently and those whose group identification is more fluid and context-dependent. |

Table 2. Implications of the changing structure of civil society.

Cross-National and Case Study Evidence

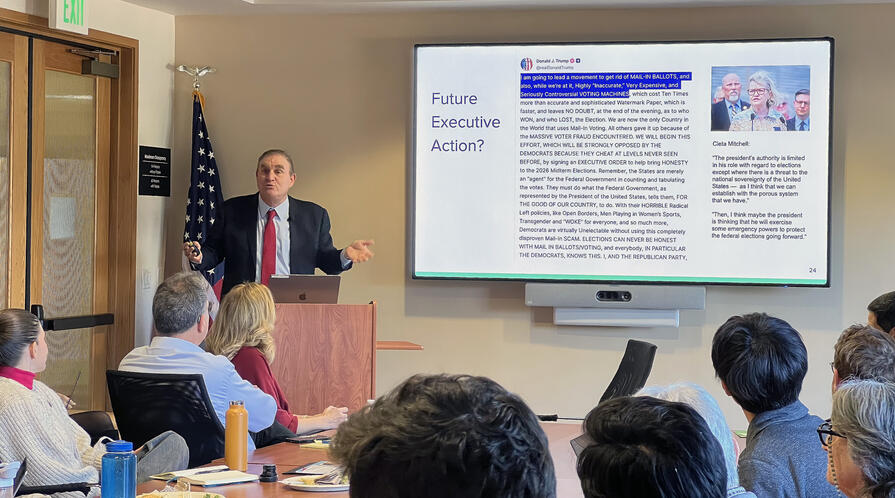

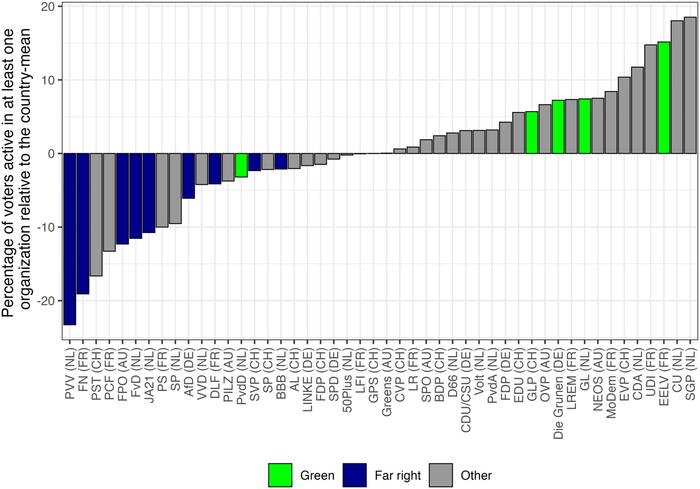

The authors then analyze cross-national data on political parties and voters in Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. One data source concerns the extent to which political parties are tied to CSOs and whether they receive large-scale CSO donations. A second source looks at whether party supporters are active in CSOs. Preliminary findings point to important differences between old, class-based parties (especially Social Democrats) and newer parties, with the latter much less tied to CSOs. However, within the new party families, Green parties are more tightly linked to CSOs than far-right parties, but there also exists variation within far-right parties. These patterns demand a more fine-grained analysis of specific cases.

Figure 2. Members of civil society organizations among the electorate of political parties in Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

Note: The figure is based on the Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2022 Dataset (2022). It uses the battery of membership in organizations and partisanship questions. In the WVS, partisanship is measured with ‘Which party would you vote for?’; in the EVS, with ‘Which political party appeals to you most?’ For this figure, the two items are treated as functional equivalents. The percentage of members is calculated from all respondents indicating sympathy towards the respective party.

Finally, the authors qualitatively analyze three distinct cases: one New Left party and both old and new far-right populist parties — the German Green Party, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), and the Alternative for Germany (AfD). Their analysis reveals key differences as regards the importance of CSOs in fostering linkage and social closure. CSOs played a key role in consolidating the Greens and SVP, whereas in the case of AfD, antipathy from German CSOs helped generate a more outsider identity.

The Greens emerged via linkages with left-libertarian social movements in the 1970s and 80s. This included groups supportive of environmental protection and feminism and opposed to nuclear proliferation. CSOs provided ideas and personnel, which helped build a sense of social closure among party supporters. This identity still persists in spite of the subsequent fragmentation of civil society.

By contrast, SVP emerged through connections to Swiss farmers' associations, rural economic networks, and local interest groups. SVP has been radicalizing since the 1990s, becoming one of Europe’s most successful far-right parties and aligning itself with Euroscepticism. SVP’s long history of rural and community penetration has helped strengthen social closure among its electorate.

Finally, AfD emerged in a more fragmented context, via its ties to right-wing protest networks. The party was a top-down vehicle that organized in response to what it saw as Germany’s mismanagement of the Eurozone crisis. AfD lacks dense connections to CSOs and has instead built informal and often volatile alliances with protesters. Many German CSOs — as well as German society more generally — explicitly oppose AfD, which has ironically helped AfD build an outsider identity because its supporters feel isolated and stigmatized.

The case studies vividly illustrate how varied CSO relationships shape cleavages and partisanship in three of the most important Western European parties.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.