Two Faces of Autonomy: How Brazilian Bureaucrats Evaluate Agency Performance

Motivation and Summary

Modern states depend upon bureaucracies effectively delivering services and enforcing regulations, from public health to environmental protection and postal services. When bureaucracies are plagued by inefficiency and incapacity and are unable to “deliver the goods,” elected representatives suffer. This can open the door for citizens to throw their support behind authoritarian leaders who promise to deliver more effectively.

A central question of bureaucratic design concerns the degree of autonomy that ‘principals’ — political actors like legislators — should delegate to bureaucratic ‘agents.’ Calibrating autonomy is crucial because principals cannot perfectly monitor or control agents, whose preferences often diverge from their own. On the one hand, highly autonomous bureaucrats may become unaccountable to their principals. Think of national security agencies that create secretive dissident watchlists or even authorize assassinations. On the other hand, bureaucracies with little autonomy will find their decision-making hamstrung by “red tape.” If public health agencies required extensive legislative approval for every aspect of vaccine delivery, infection rates would skyrocket. How, then, can bureaucracies be designed to achieve their goals, creatively respond to new problems, and minimize corruption, all while being perceived as legitimate?

In “Calibrating autonomy,” Katherine Bersch and Francis Fukuyama disaggregate the concept of autonomy into two facets (independence and discretion), present hypotheses concerning how each facet relates to capacity and quality, and then test these hypotheses, primarily using survey data from Brazilian bureaucrats. Their findings caution against overly blunt efforts to calibrate autonomy across multiple bureaucracies, suggesting instead that policymakers should understand a given agency’s capacity to perform.

Argument and Hypotheses

The article builds on earlier research by co-author Francis Fukuyama, who in 2013 hypothesized a key moderating role for bureaucratic capacity in the relationship between autonomy and quality. Briefly, low-capacity agencies — lacking expertise and resources — will likely struggle to utilize their autonomy and deliver, whereas high-capacity bureaucracies will deliver effectively for opposite reasons. However, autonomy is itself a complex concept that ought to be disentangled before one can begin to spell out how it is linked to delivery.

Independence, the first “face” of autonomy, concerns the degree to which bureaucrats are constrained by actors who are close to politics, such as elected leaders or politically-appointed agency heads. More independent bureaucrats might allocate waste management contracts on the basis of cost-effectiveness or service quality records. Less independent bureaucrats might allocate according to the whims of politicians who wish to reward their allies. The degree of independence is oftentimes a function of the number and extent of political appointees in a given agency.

The second face of autonomy is discretion, or rather, the extent to which agencies are constrained by laws, rules, or protocols. Waste management agencies with limited discretion may struggle to respond to sporadic garbage pile-ups, whereas those with high discretion may set unpredictable collection schedules.

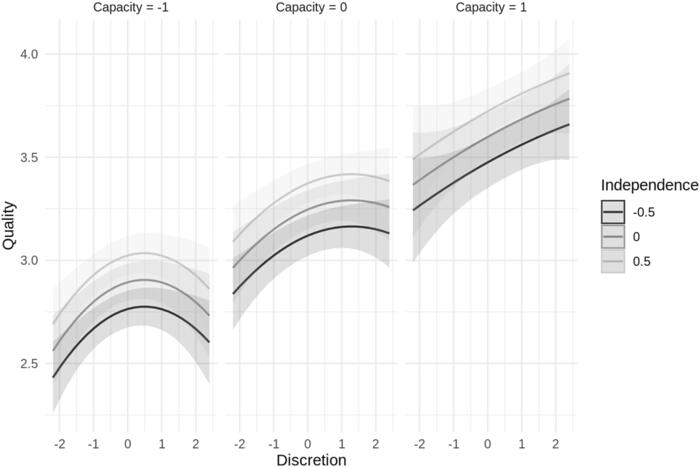

These two faces of autonomy lead to different expectations about how they are connected to quality. The authors hypothesize that independence and quality stand in a linear and positive relationship: agencies that are more unconstrained by political actors will deliver more effectively. By contrast, discretion and quality stand in a non-linear or “Goldilocks” relationship: too few and too many constraining rules will reduce quality. Following Fukuyama’s earlier research, capacity moderates these relationships; for example, less independence in specifically low-capacity agencies may strengthen quality, perhaps in cases where legislative actors are able to appoint highly qualified experts.

Methods and Findings

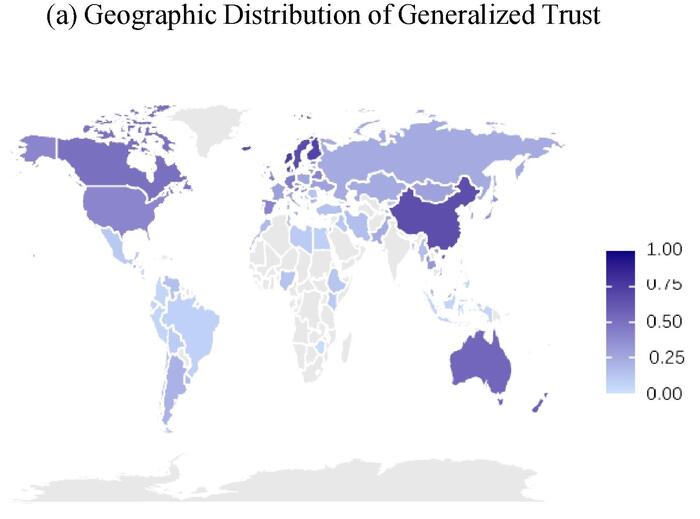

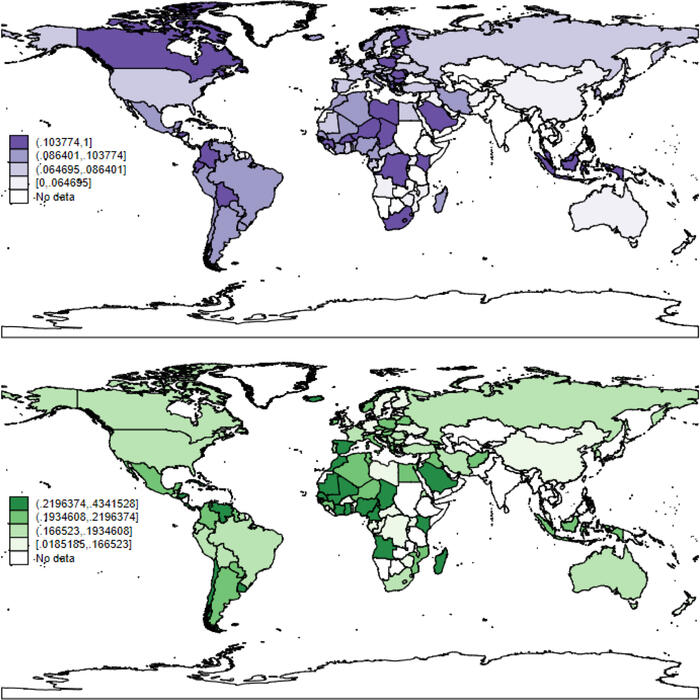

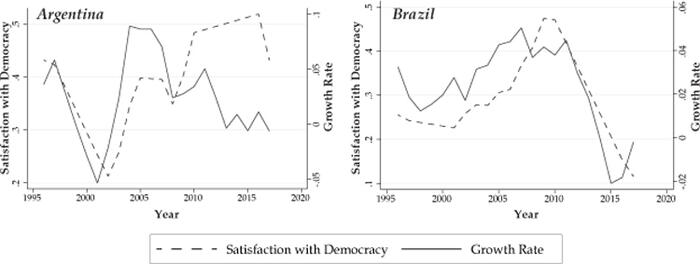

The authors select Brazil as their case, in part because it exhibits considerable internal variation in bureaucratic quality: some agencies are professional while others are incompetent. By focusing on one country, they avoid comparing fundamentally different national bureaucratic contexts. Further, selecting Brazil — with both strong and weak bureaucracies — reduces ‘selection biases,’ i.e., mistaking characteristics of only high- or low-quality agencies as causes of overall performance. From a global standpoint, Brazilian bureaucracies are solidly middle-ranged, neither outstanding nor abysmal.

The main empirical part of the paper involves a 2018 survey of over 3200 Brazilian federal bureaucrats. About 60% of the respondents are political appointees and 40% are civil servants, which enables looking at bureaucrats who stand in different relationships to political actors. The authors exclude military personnel, teachers, nurses, and local police officers.

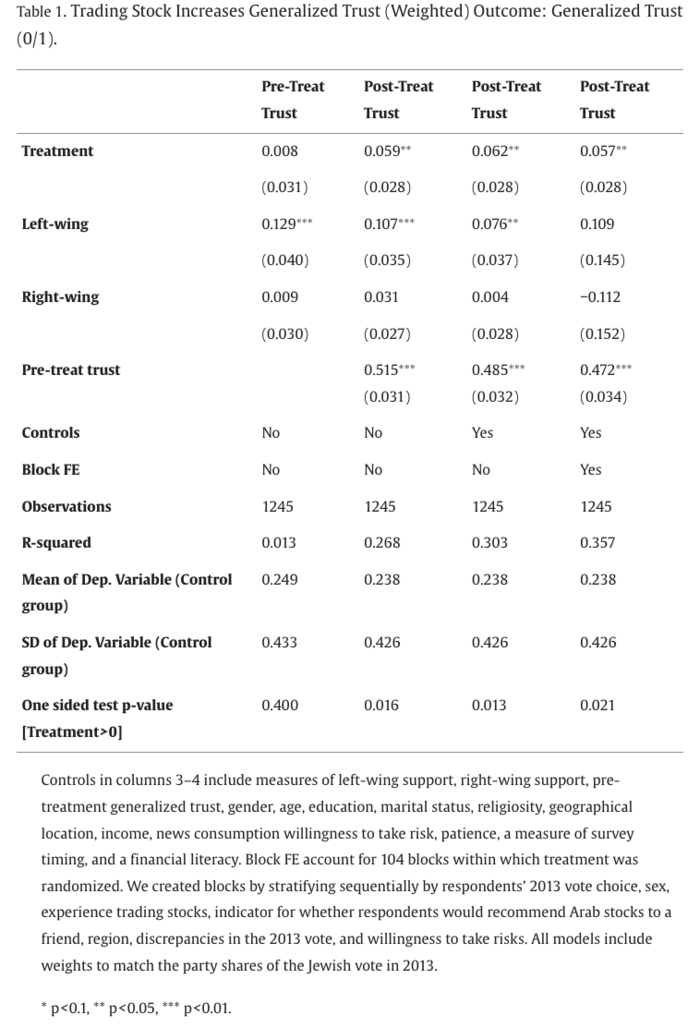

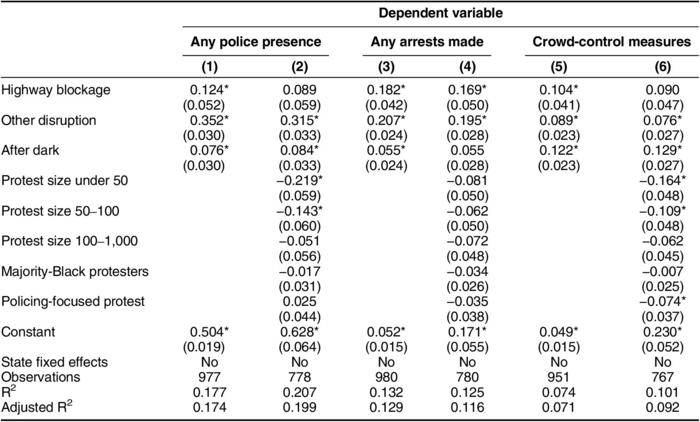

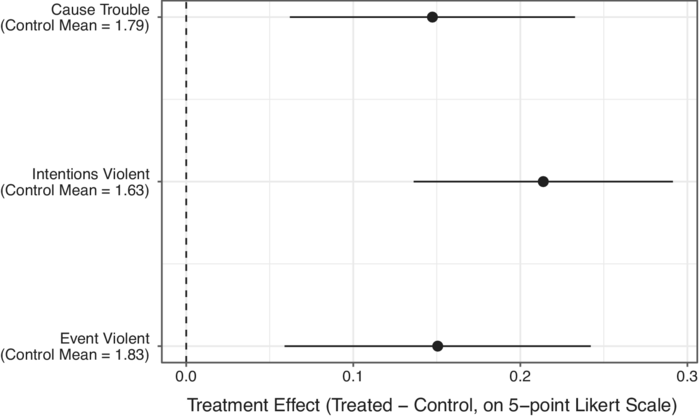

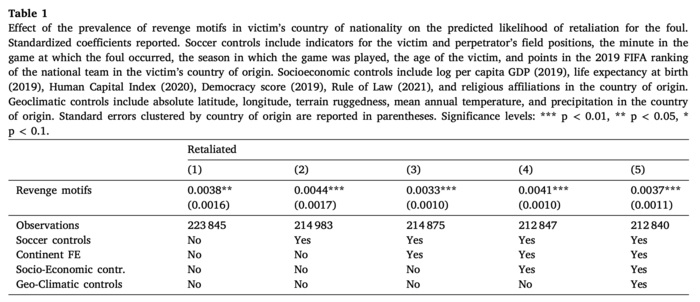

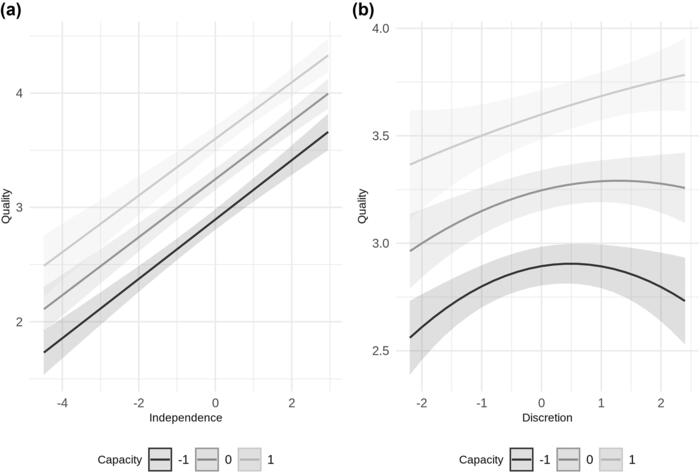

As hypothesized, respondents’ perceptions of agency independence increase their perceptions of quality in a linear way. This finding likely reflects Brazil’s coalitional style of government: politicians benefit electorally from strong government performance; without bureaucratic independence, political pressure and influence from the many coalition partners would likely hinder bureaucrats and weaken performance. Meanwhile, perceptions of discretion align with the authors’ non-linear expectations.

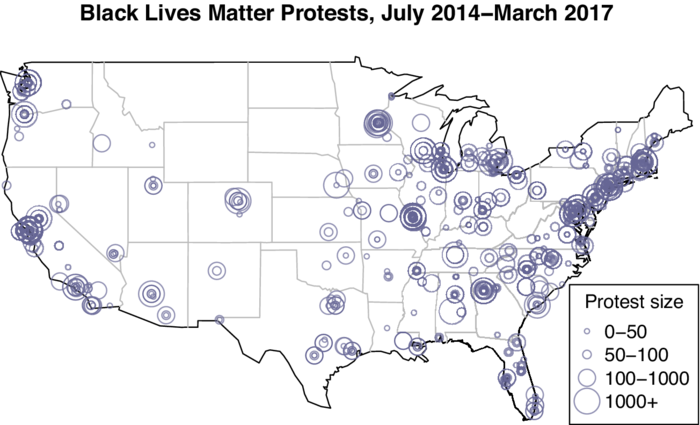

Figure 3: (a) Impact of independence on quality at varying levels of capacity. (b) Impact of discretion on quality at varying levels of capacity.

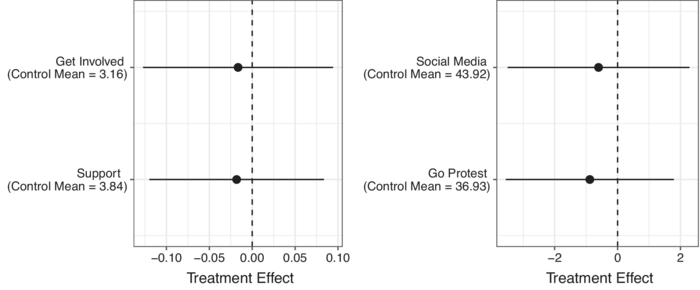

These findings are mediated by capacity, which the authors measure in terms of resources, career length, salaries, and the proportion of agents in core or expert careers. The findings hold even when controlling for political factors like party membership or appointment type (political vs. civil servant), individual characteristics such as gender or years of service, and agency differences, including budget or size. These controls are based on administrative data from over 326,000 bureaucrats across Brazil’s 95 most important federal agencies.

Figure 4: Quality at varying levels of capacity.

Contributions and Implications

“Calibrating autonomy” makes important conceptual and empirical contributions to our understanding of bureaucratic performance. By disaggregating the concept of autonomy into independence and discretion, it helps make sense of seemingly contradictory empirical findings, namely that both minimally and highly autonomous bureaucracies perform well. And by evaluating their hypotheses about the two faces of autonomy using Brazilian data, the authors guard against selection biases or problems from comparing countries with quite different bureaucratic landscapes.

The paper serves as a caution against overly simplistic or blunt “solutions” to poor bureaucratic performance. Merely limiting discretion or increasing legislative oversight can make matters worse if the relevant bureaucratic culture is not properly understood, especially when it comes to capacity.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4-minute read]