Conditional Cash Transfers, Poverty, and Democracy in Latin America: Successes and Challenges

Conditional Cash Transfers, Poverty, and Democracy in Latin America: Successes and Challenges

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4-minute read]

Argument & Key Findings

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) have been a widespread and effective tool in reducing poverty in Latin America. CCT programs transfer cash to the poor on the condition that recipients engage in beneficial behaviors, like enrolling their children in school, vaccinating them, or taking them to see a physician. CCTs aim to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty, especially among women. Indeed, women are central to CCTs as they are often responsible for children’s health and nutrition as well as ensuring that they remain enrolled in school.

Alberto Díaz-Cayeros reviews the scholarship on CCTs in Latin America, where much of that research had originated, shedding light on these programs’ workings and effects. Particular focus is given to how CCTs have helped overcome shortcomings of democratic systems, including ‘clientelism,’ broadly understood as the practice of politicians trading goods or services for votes. Despite CCTs’ broad success, challenges persist, especially regarding their use to mitigate poverty that is concentrated in rural areas as well as among indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples. The reader learns that CCTs are deeply interwoven with the behavior of politicians and the mobilization of social groups for political goals. CCTs are very malleable tools, having been adapted to the advent of COVID-19 when contagion and income loss were prevalent among the poor. CCTs have been one of the most rigorously evaluated interventions by social scientists. Most generally, they have reduced poverty, inequality, and infant mortality, while increasing school enrollment and nutrition.

Conceptualizing & Measuring Poverty

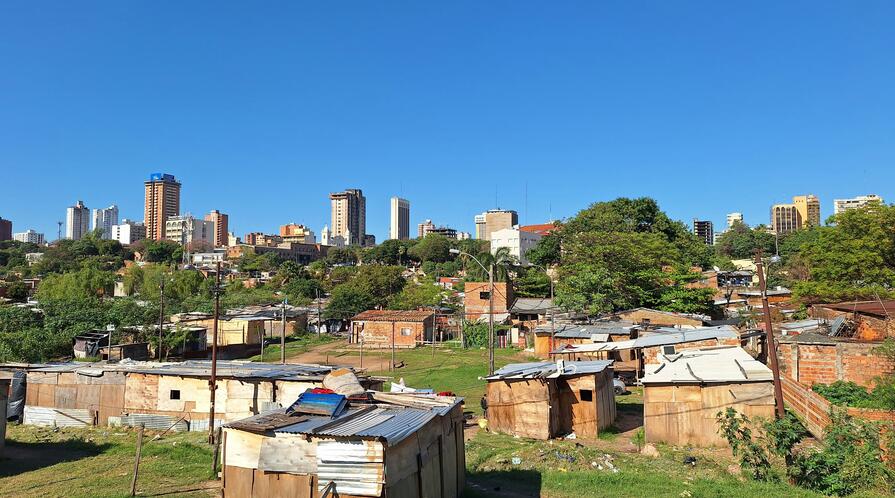

Díaz-Cayeros builds an incredibly rich historical overview of poverty in Latin America. This includes both its persistence and its dramatic decline in recent decades, CCTs having played a key role in the latter process. However, national-level declines obscure the wide disparities that persist at the subnational level and among historically marginalized communities. In addition, efforts (like CCTs) aimed at tackling poverty have often failed to address inequality, because social spending in Latin America has at times been regressive, i.e., taking resources from the poor and giving them to the middle and upper classes. Meanwhile, fiscal resources are often transferred to poor regional governments, as opposed to the individuals within them.

Poverty persists in part because of ‘poverty traps,’ a technical concept tied to factors like limited access to credit and education as well as poor health. These problems are especially pronounced in rural areas, which are often isolated from economic activity, lack the social mobility of cities, and tend to feature systemic exclusion along ethno-racial lines. The measurement of poverty has become increasingly sophisticated, moving beyond income to incorporate assets, basic needs, and geospatial data. The upshot of Díaz-Cayeros’ overview is that measurements of poverty, which any evaluation of CCTs must incorporate, often fail to account for poverty traps and their concentration among distinct groups in specific areas.

Background & Variation

Díaz-Cayeros examines the historical roots of CCTs, highlighting the role of 20th-century Latin American governments in replacing Catholic charities and philanthropists as the primary actors addressing poverty. These governments sought to target primarily urban poverty, owing to large-scale processes of internal migration, which moved workers away from agriculture and into factories and the informal economy. This helps explain the persistence of rural poverty. State social spending was undermined by the Latin American debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s, which disproportionately harmed the rural poor. The 2010s commodity boom enabled a re-expansion of social spending, although these programs continued to be insufficient to lift historically marginalized peoples out of poverty. The creation of CCTs by Mexican economist Santiago Levy in the 1990s can thus be placed against this backdrop of poverty, austerity, and labor market change.

CCTs have been widely adopted across Latin America by governments of different partisan leanings. One important determinant of this process has been fiscal constraint: because CCTs are relatively inexpensive, wealthier countries adopted them later. It should also be noted that effective CCTs depend on effective states, which provide, among other things, the hospitals and schools that recipients must utilize. By the mid-2020s, nearly 60 programs existed across Latin America, varying widely in terms of the share of beneficiaries of the total population. Countries that adopted CCTs early on do not necessarily have larger shares of beneficiaries, and larger shares don’t necessarily mean a given CCT is effectively helping the poor.

Clientelism & Democracy

One of the most important political aspects of CCTs is their potential resistance to ‘clientelism.’ What this means is that universal and automatic criteria for CCT recipients can limit the ability of politicians to trade particular benefits for votes. As such, CCTs have helped improve Latin American democracy, partly because politicians who ‘credit-claim’ for implementing CCTs can be more readily held accountable. On the ground, politicians still find ways to perpetuate clientelism, for example by manipulating the distribution of non-CCT goods like water cisterns. However, the broader implications of CCT are significant: as citizens’ cash needs are met, they can more meaningfully participate in the democratic process.

Future Research

Díaz-Cayeros posits an agenda for future research. These include: (1) the ways that continued discrimination against indigenous and Afro-descendant communities may require changes to the design of CCTs, (2) the ways that CCTs can be complemented by private charities and NGOs; the ways that expansions to CCT might bring Latin American governments closer to providing a universal basic income, and (3) the sources of Latin American citizens’ support for CCTs, whether owing to moral sensibilities, fear of deprivation, or otherwise. Ultimately, CCTs have been broadly successful and adaptable, improving both the economic standing and political efficacy of poor citizens. Their long-term success depends upon addressing the victims of systemic exclusion and intergenerational poverty.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.