Resource Concentration and Authoritarianism

On February 12, Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), the Europe Center, and the Hoover Institution hosted Lucan Way, Distinguished Professor of Democracy at the University of Toronto, for a seminar titled “Economic Dependence and Authoritarianism: Russia in Comparative Perspective.” The talk, part of the REDS (Rethinking European Development and Security) series, examined the structural relationship between state resource concentration and democratic outcomes, using Russia as a central case while situating it within broader comparative patterns.

Way’s core argument centered on a simple but powerful proposition: when economic resources are concentrated in the hands of the state, autocracy becomes more likely; when resources are dispersed outside the state, democracy becomes more feasible. The key mechanism linking economic structure to regime type is the strength — or weakness — of countervailing societal power. Resource concentration generates societal dependence on political leaders. Citizens dependent on public-sector employment or state benefits face high personal costs for political opposition, including loss of income or access to essential services. Similarly, business elites reliant on state licenses, contracts, or regulatory goodwill incur substantial risks if they challenge incumbents. The result is weak opposition, limited activist networks, minimal independent funding, and fragile civil society organizations.

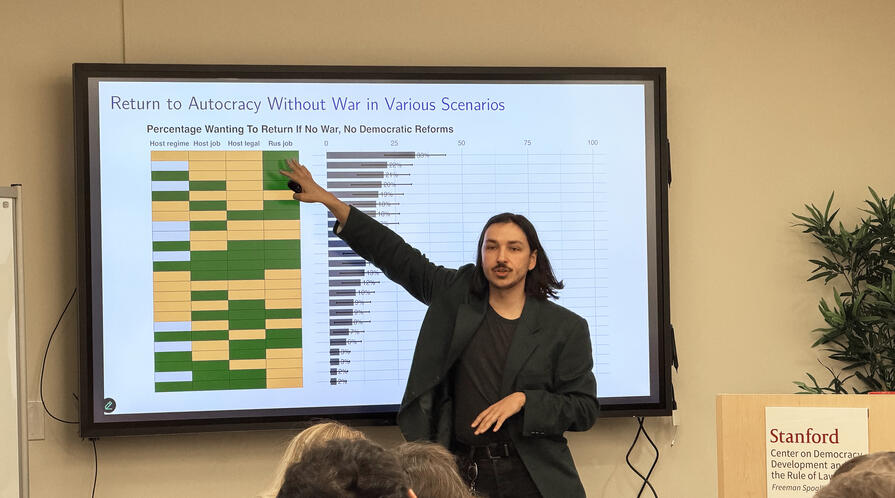

Way situated this framework within three major literatures on authoritarianism. First, underdevelopment (Lipset 1959; Przeworski et al. 2000) remains strongly associated with autocracy: roughly 70 percent of poor countries were autocratic between 2000 and 2021. Second, oil wealth (Ross 2001; Bellin 2004) produces an even starker pattern: about 90 percent of petrostates were authoritarian in the same period. Third, statist or weak private-sector economies (Fish 2005; Greene 2007; Arriola 2013; Rosenfeld 2021) show similar tendencies, with roughly 80 percent of the most statist countries classified as autocratic. Despite their differences — very poor African states, wealthy Middle Eastern petrostates, and middle-income statist regimes — the underlying mechanism is the same: resource concentration fosters weak countervailing power.

Russia exemplifies this structural dynamic. While the 1990s appeared to feature strong countervailing forces, including powerful oligarchs credited with supporting Boris Yeltsin’s reelection, Way argued that these actors were in fact institutionally weak. Russia’s private sector relied heavily on state connections in a system with weak courts and manipulable regulatory frameworks. The imprisonment of Mikhail Khodorkovsky after he challenged Vladimir Putin underscored the vulnerability of even the wealthiest economic actors. The broader business community remained largely passive, reflecting structural dependence rather than autonomous strength.

Statism further entrenched authoritarian control. A state-dependent middle class and political parties reliant on Kremlin financing limited the development of robust opposition. In oil-rich systems, public-sector employment and distributive benefits deepen citizens' dependence, while governments remain fiscally insulated from private-sector pressures. In underdeveloped postcolonial contexts, even modestly financed states wield disproportionate leverage over fragile economies, facilitating cooptation and repression.

Preliminary statistical evidence using V-Dem measures of “resource concentration” supports these claims. State ownership or control over key sectors correlates strongly with authoritarianism, high pro-incumbent mobilization, low opposition mobilization, media control, and weak civil society. Way acknowledged complications, including endogeneity: autocrats often increase resource concentration through nationalization or expansion of public employment. Nevertheless, certain structural conditions — such as large oil reserves, extreme underdevelopment, or historically weak private sectors — make concentration more feasible ex ante.

In conclusion, Way emphasized that autocracy is not inevitable in such contexts. However, where countervailing societal power is weak, imposing authoritarian rule becomes far easier. Across diverse regimes, economic dependence constitutes a common mechanism of authoritarian control — whether through business capture of the state or state capture of business.

Read More

Lucan Way examines the structural relationship between state resource concentration and democratic outcomes, using Russia as a central case while situating it within broader comparative patterns.

- In a REDS (Rethinking European Development and Security) Seminar co-hosted by the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, The Europe Center, and the Hoover Institution, Lucan Way examined how state resource concentration shapes authoritarian and democratic trajectories.

- He argued that economic dependence weakens opposition, civil society, and independent business, limiting countervailing societal power.

- The discussion situated Russia within comparative research on statism, oil wealth, and the links between underdevelopment and the durability of authoritarianism.