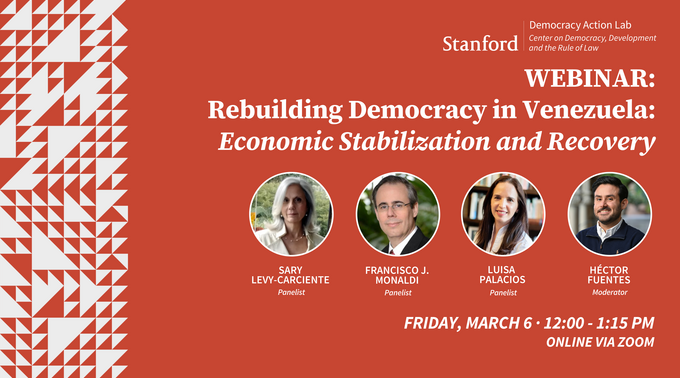

DAL Webinar Series — Rebuilding Democracy in Venezuela: Economic Stabilization and Recovery

"Rebuilding Democracy in Venezuela" is a four-part webinar series hosted by CDDRL's Democracy Action Lab that examines Venezuela’s uncertain transition to democracy through the political, economic, security, and justice-related challenges that will ultimately determine its success. Moving beyond abstract calls for change, the series will offer a practical, sequenced analysis of what a democratic opening in Venezuela would realistically require, drawing on comparative experiences from other post-authoritarian transitions.

Venezuela stands at a critical juncture. Following Nicolás Maduro's removal in January 2026, the question facing Venezuelan democratic actors and international partners is no longer whether a transition should occur, but how it could realistically unfold and what risks may undermine it. While the first session focused on the political challenges of transition, this second conversation examines the economic foundations of democratic viability. Sustainable political change in Venezuela will depend critically on the country’s ability to stabilize its economy, restore growth, and generate tangible improvements in living conditions. At the same time, economic recovery itself is deeply conditioned by political uncertainty, institutional fragility, and governance constraints. Understanding this interaction is essential for designing realistic pathways forward.

This webinar seeks to provide a serious, policy-relevant discussion of the economic constraints shaping Venezuela’s future and the conditions under which recovery could become politically sustainable and socially inclusive. Bringing together expertise in energy economics, macroeconomic stabilization, development policy, and political economy, the session aims to inform Venezuelan actors, international partners, scholars, and practitioners with grounded and realistic insights.

SPEAKERS

- Sary Levy-Carciente, Research Scientist, Adam Smith Center for Economic Freedom at Florida International University

Attracting investments and developing the non-oil economy

Luisa Palacios, Adjunct Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia School of International Affairs

Energy policy and finance

- Francisco J. Monaldi, Fellow in Latin American Energy Policy, Baker Institute and Director, Latin America Energy Program at Rice University

- Oil and gas sector: requirements for a sustainable increase in production capacity

- Moderator: Héctor Fuentes, Visiting Scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University

Online via Zoom. Registration required.

Join us for the second event in a 4-part webinar series hosted by the Democracy Action Lab — "Rebuilding Democracy in Venezuela" Friday, March 6, 12:00 - 1:15 pm PT. Click to register for Zoom.