Player Retaliation and Referee Sanctioning in Association Football

Motivation

Retaliation (or the threat thereof) is a central component of human behavior. It plays a key role in sustaining cooperation — such as in international organizations or free trade agreements — because those known to retaliate come to acquire a reputation of being hard to exploit. But how does the use and function of retaliation vary across cultures, and how does it interact with formal forms of punishment?

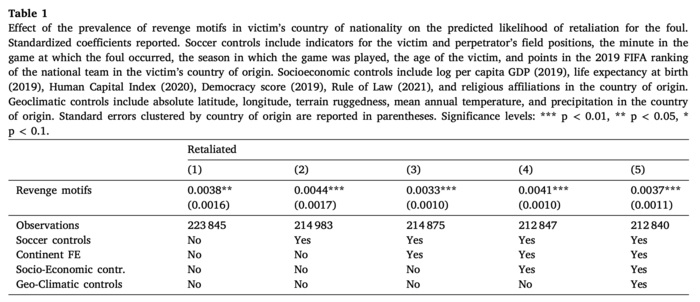

In “Cross-cultural differences in retaliation: Evidence from the soccer field,” Alain Schläpfer tackles these questions using data on retaliation from association football. Retaliation is simply defined in terms of fouling: player B retaliates against player A if and only if, after A fouls B, B then fouls A. Among other findings, Schläpfer shows that players from cultures emphasizing revenge are more likely to retaliate on the football field. This form of ‘informal punishment’ by players also interacts with ‘formal punishment’ by referees: retaliation by B is less likely when A is sanctioned with a yellow card. Schläpfer’s paper increases our knowledge of the causes and consequences of retaliation, while showing how informal cultural norms interact with the formal rules of football.

Data

Schläpfer creates a data set of fouls committed over three football seasons (2016-2019) in nine of the world’s top professional men’s leagues. This includes the European leagues of Premier League (England), Serie A (Italy), Bundesliga (Germany), LaLiga (Spain), and Ligue 1 (France), as well as Série A (Brazil), Liga Profesional (Argentina), Liga MX (Mexico), and Major League Soccer (United States). The dataset comprises 9,531 games, 230,113 fouls committed by 10,928 unique perpetrators from 139 countries against 11,115 unique victims from 137 countries.

Because Schläpfer hypothesizes that being from more revenge-centric cultures explains on-field retaliation, the key independent variable is measured using a dataset from Stelios Michalopoulos and Melanie Meng Xue that identifies revenge motifs in a culture’s folklore. Examples of this include supernatural forces avenging human murders or animals avenging the death of their friends by humans. Schläpfer uses a host of other independent variables, such as country-level survey data about the desire to punish — as opposed to rehabilitate — criminals, which is also theoretically linked to revenge. As stated above, retaliation is measured in terms of fouls committed. Schläpfer shows that there is substantial variation in retaliation rates among players from different countries, from Gabon (8%) to Iceland (31%). Can the folklore in the country of origin explain the behavior of players on the field?

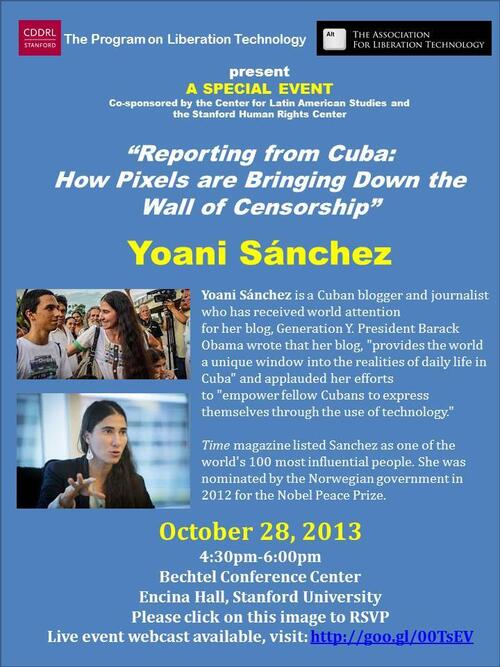

Fig. 1. The share of fouls retaliated in soccer games (top) and the prevalence of revenge motifs in folklore (bottom). Both variables tend to have higher values for players and folklore from the Middle East, Central Africa, Eastern Europe, and parts of South America.

Findings

Retaliation:

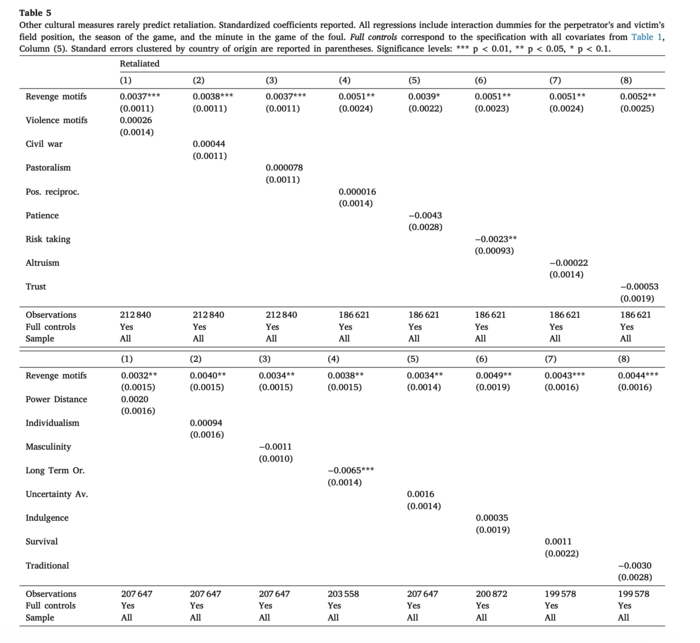

Schläpfer finds evidence that players from cultures that value revenge are indeed more likely to retaliate for fouls. However, they are not more likely to commit fouls overall, cautioning us against conflating the concepts of retaliation and violence. Indeed, Schläpfer demonstrates that motifs of violence in a culture's folklore do not predict retaliation. Players are also found to be more retaliatory early on in a game, which is consistent with its use as a signal or aspect of one’s reputation. In other words, retaliation serves to deter future fouls. Victims of fouls also retaliate quickly. Indeed, retaliation rates are stable or slightly increasing during the first 30 minutes of a game, but then fall consistently thereafter.

Evidence is also provided to show that retaliation deters future transgressions: perpetrators are less likely to foul again if victims retaliate for the initial foul. However, this deterrence finding is only observed when the perpetrator is from a revenge culture. In other words, for retaliation to support cooperation (the absence of fouls), players must share a similar cultural background.

Schläpfer’s findings hold even when soccer-related or socioeconomic factors are taken into account. Further, the paper considers, but finds little support for, alternative explanations of why retaliation varies. These include that some teams encourage players to retaliate more or employ more players from revenge cultures. Further, retaliation does not appear to be driven by emotions; otherwise, it would be less likely to occur after halftime when players have had a chance to cool down, but this is not the case.

Informal and Formal Sanctioning:

Finally, Schläpfer analyzes the interaction between player retaliation and refereeing. Most importantly, retaliation is significantly less likely if a foul is sanctioned with a yellow card. This illustrates the theoretical principle of formal punishment “crowding out” informal punishment, such as religious excommunication, which carries greater weight than social shunning or police fines compared to peer pressure. Both retaliation and referee sanctioning are shown to reduce the frequency of repeated offenses by perpetrators, especially among players from revenge cultures. However, Schläpfer finds that formal sanctioning is roughly three times more effective than retaliation. This suggests that football referees are doing a better job managing conflict between players than players themselves.

Schläpfer concludes by mentioning a few of the paper’s limitations. First of all, retaliation is measured only by what referees sanction. However, referees may miss crucial incidents for which retaliation is a response, such as Zinedine Zidane’s 2006 World Cup headbutt after a verbal insult (that was not sanctioned). This is important because individuals from revenge cultures are likely to be particularly offended by verbal insults. Second, the paper does not capture retaliation that occurs across games played by the same teams over time, particularly when rivalries and hostilities have intensified. Similarly, it does not account for preemptive retaliation that does not follow a foul. Ultimately, Schläpfer deepens our understanding of retaliation in a domain where many would expect it not to operate or to do so with minimal significance. The article impressively marshals large-scale data from both sports and cultural history to clarify the causes and consequences of retaliation.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4-minute read]