Economic Retaliation and the Decline of Opposition Quality

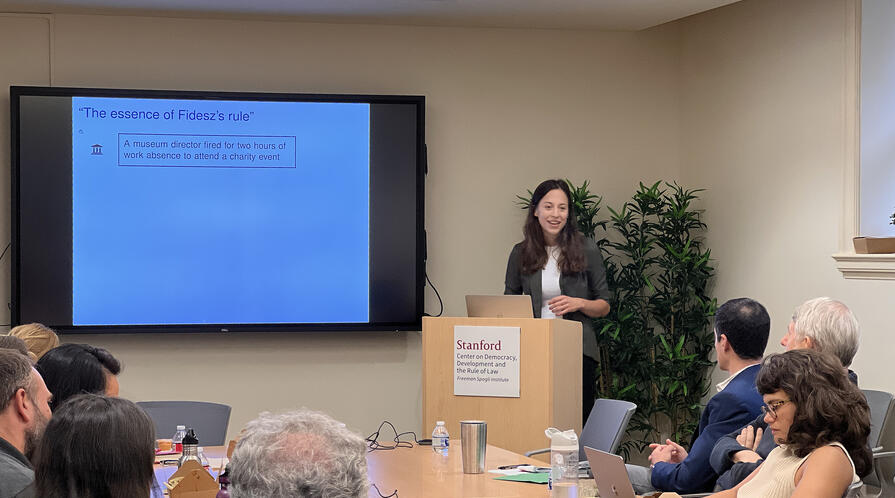

On November 13, 2025, Hanna Folsz, a Pre-Doctoral Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, presented her research on “Economic Retaliation and the Decline of Opposition Quality.” This CDDRL research seminar built on Folsz’s focus on authoritarianism and democratic backsliding.

Hungary has experienced significant democratic decline, spurred by Fidesz Party leader Viktor Orbán’s rise to power in 2010. Since then, armed with a parliamentary supermajority, the Fidesz Party has taken several democratic-eroding actions: rewriting electoral rules, capturing the courts and media, and repressing independent civil society. Prior to these actions, Hungary had close elections. But after 2010 and the Fidesz Party’s changes, elections are no longer close. Illiberal populists worldwide — like Trump, Bolsonaro, Netanyahu, and Erdoğan — look to Orban’s agenda as a template on how to dismantle democracy, and how to maintain voter support while doing so. In Hungary, opposition politicians, candidates, advocates, and voters do not face violence or arrests for their political views. However, Folsz argues that there exists a pervasive fear in opposition circles stemming from the potential for economic retaliation. Folsz recalls examples of this from interviews she conducted in Hungary.

In Miskolc, a city in Northeastern Hungary, the local head of the socialist party recalled a story from 201,9 when the party was able to convince a well-respected businessman to run for a seat. However, after agreeing to become a candidate, the candidate’s wife said, “Are you out of your mind? Don’t you think about your daughter? She will lose her job if you do this!” The couple’s daughter worked at a local passport office, a state-dependent job. The candidate withdrew his candidacy. His replacement was an elderly woman who was unable to campaign. The socialist party lost the race.

Another interviewee, Tibor Zaveczki, ran as an opposition candidate. He was fired from a state-owned company for doing so. Zaveczki took the case to court, armed with secret recordings of his firing. The recording included a conversation between Zaveczki and his manager, in which his manager said: “The city leadership decided not to continue working with you in our company.” Zaveczki asked, “So, to put it plainly, was my mistake that I openly declared I was in the opposition?” His manager responded, “Of course, that matters. That’s obvious. You’re not stupid.”

Folsz identified that existing literature on democratic backsliding often focuses on the incumbent's strategy to dismantle democratic institutions and on why voters tolerate these actions. However, the role of opposition parties is rarely addressed. Folsz went into her research asking the question: Why do opposition parties struggle to challenge aspiring autocrats in elections? Folsz asserts that the main reason is that opposition parties have a growing political talent deficit in democratic declines, driven by an authoritarian strategy that Folsz calls elite economic coercion. This entails a credible threat of economic retaliation for opposition candidacy that discourages opposition political entry, reduces opposition candidate quality, and weakens opposition parties.

Folsz outlines two types of economic retaliation. The first is employment-oriented, where state-sector employees might face fear of dismissal from their job, demotions, or lack of promotions if they or a family member runs for office with the opposition party. The second is enterprise-oriented, where business owners might face a credible threat in the form of tax audits, the cancellation of state contracts, or the denial of grants, or even be blacklisted by suppliers or clients. Folsz outlines the effects of elite economic coercion, stating that the coercion leads to a higher cost of candidacy, which then leads to deterrence of political entry. This results in a lower opposition candidate quality and ultimately weakens opposition parties.

Folsz then empirically tested these three steps of the theory: retaliation, deterrence, and endogenous entry. Using tax enforcement as a proxy for economic retaliation, Folsz found a significant increase in tax enforcement in firms that had links to opposition candidates, and found the effect stronger with opposition-owned firms. Folsz also found that these firms were less likely to stay in business and decreased in their number of employees and profit compared to incumbent party-linked firms after the firm owner’s or director’s political entry. State dependence is a very central deterrent of candidacy– a survey experiment shows that state dependents are about 13 percent less likely to join opposition politics as candidates. Folsz used data on candidate background to show that the quality of opposition candidates declined compared to the incumbent Fidesz Party candidates during Hungary’s democratic decline.

Folsz concluded by stressing that the weakening of opposition parties is key to authorization, and candidate recruitment is a central challenge for opposition parties during democratic decline.

Read More

CDDRL Pre-doctoral Fellow Hanna Folsz presented her research, which builds on her focus on authoritarianism and democratic backsliding.