Emigration Policy Under Authoritarianism and Incentives to Break the Law

Introduction and Contribution:

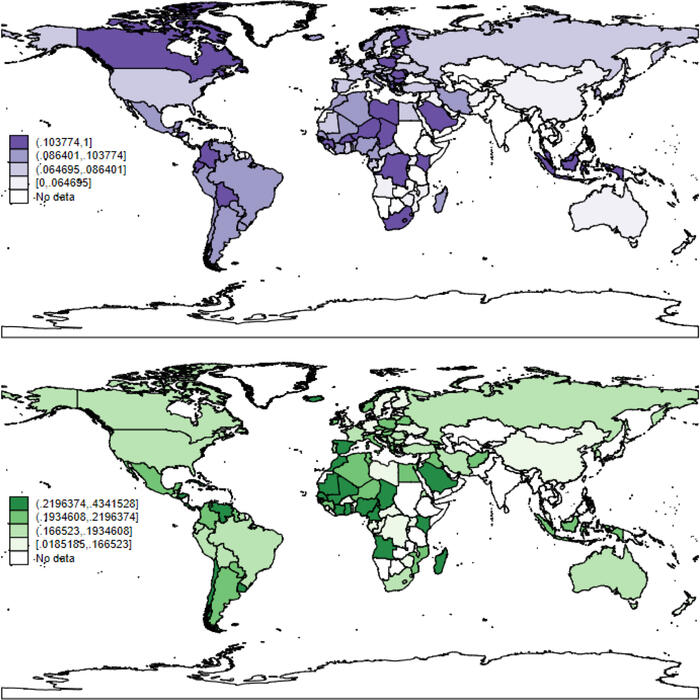

Authoritarian regimes are often reluctant to let their citizens leave: 79% of autocracies restrict emigration compared to only 4% of democracies. This reluctance is understandable, as migration deprives rulers of talent, resources, and implied consent to the system. Yet autocracies do change their emigration laws. What are the consequences of these changes?

In “A Little Lift in the Iron Curtain,” Hans Lueders examines how a 1983 emigration reform in socialist East Germany (German Democratic Republic, GDR) affected crime rates in the country. The reform permitted about 62,500 citizens to exit the GDR over a short period of time — mostly to reunite with their families in West Germany. Lueders asks how this emigration affected crime. This is a natural outcome to consider because the former GDR, like many autocracies, used the emigration system to filter out individuals seen as criminals or “undesirables.” Unauthorized exit was criminalized, and some citizens committed crimes precisely to signal that they should be allowed to leave.

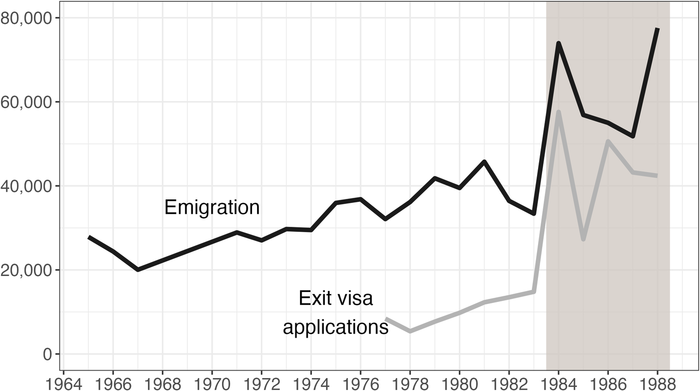

Figure 1: Consequences of the 1983 Emigration Reform

Note. This figure reports the number of first-time exit visa applications per year (gray line [Eisenfeld 1995, 202]) and annual emigration from the former GDR (black line; data collected by the author). The period after the emigration reform is emphasized.

Lueders shows that the effects of emigration following the 1983 reform on criminal activity depended on the type of crime. Ordinary kinds of crime — those not committed for political motifs — declined after the reform. However, border-related crimes increased sharply. This is ostensibly because those “left behind” (i.e., unable to take advantage of the 1983 reforms) resumed lawbreaking in order to pressure the regime to let them out as well. An analysis of petitions submitted to the state supports the idea that emigration raised demand for emigration.

The paper makes important contributions to our knowledge of authoritarianism and migration. For one, it shows how policies enacted to temporarily satisfy domestic or international audiences can backfire, later increasing the state’s burden. Autocrats may behave strategically in the short run, yet their choices can have powerful, unanticipated consequences in the years ahead. Otherwise, “strong” and repressive autocracies like the former GDR may struggle to address migratory pressures and be too inflexible to switch course after negative consequences become apparent.

Safety Valves and Reform in East Germany:

Social scientists have argued that emigration policy under authoritarianism can serve as a “safety valve,” allowing or forcing the exit of those who threaten the stability of the regime. In addition, requiring citizens to apply for exit visas acts as a “screening mechanism” because applying is politically costly; those who keep applying reveal themselves to be potential troublemakers whose exit ought to be permitted. Lueders provides evidence that the costs of applying for exit visas were indeed high in the former GDR: applicants (and sometimes their families) were intimidated and harassed by secret police, expelled from universities, and demoted or fired. The state also tried to “win over” prospective emigrants, showing them reports about the allegedly dismal living conditions in West Germany or letters from East German refugees begging authorities to return to the GDR.

Importantly, officials considered how emigration would influence the GDR’s stability, looking for those who opposed the country and its socialist vision. Many applicants realized this and thus sought to publicly challenge the regime, for example, by leaving socialist mass organizations or abstaining from voting. Committing crimes thus raised one’s chances of successfully emigrating. East Germans watched peers and family members break the law to force their exit, learning that the system encouraged and rewarded criminality.

After Germany’s division into two, many East Germans preferred the economic and political freedoms found in democratic West Germany. The government thus grew concerned: most émigrés were young and educated, and their exit undermined the GDR’s claims that it was popular and that socialism was the superior politico-economic system. Accordingly, emigration was criminalized in 1952, and the GDR began erecting physical barriers, culminating in the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. Emigration plummeted to between 25,000 and 40,000 per year thereafter.

Emigration remained severely limited until the early 1980s, when international pressure — from both West Germany and the Soviet Union — to reform its emigration system began to build. Ultimately, in September 1983, the GDR conceded and recognized the right of all citizens with family abroad to apply for an exit visa.

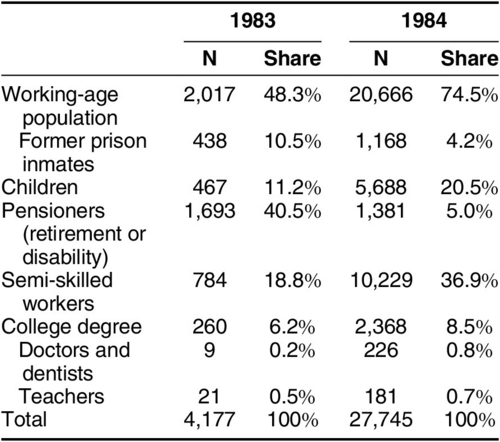

After the reform, exit visa applications and departures surged, the largest wave since the Berlin Wall’s construction. Emigration patterns evidenced a clear demographic shift: émigrés were less likely to be retired or to have formerly served in prison, while working-age East Germans made up 75% of emigrants, up from 49%. The state viewed this emigration wave as a welcome opportunity to get rid of criminals and political enemies. However, it underestimated the long-term consequences of offering some citizens a way out.

Table 1: Comparison of Emigrants in 1983 and 1984 (January to June of each year)

Data and Findings:

To measure the effects of the 1983 policy on crime, Lueders presents crime data from 1976 to 89. He divides crime into “ordinary,” e.g., against state property or persons, and “political” crimes, e.g., the use of force against state officials, treason, and, importantly, illegal border crossings. Two of Lueders’ key hypotheses for our purposes are that emigration reform led to (1) a decline in ordinary crime, because the GDR effectively removed so-called troublemakers (the safety valve mechanism), and (2) a rise in border crimes, because those left behind were willing to break the law in order to exit (the demand mechanism).

The statistical analysis — consisting of comparing places with varying emigration rates — is consistent with both hypotheses. For the most part, ordinary crime declined after 1983. By contrast, border crime also initially declined, but this pattern dramatically reversed within two years. By 1987, border crimes began to rise significantly in places that had experienced a lot of emigration in the initial wave. Lueders thus provides evidence that in the short run, emigration indeed functioned as a safety valve (i.e., criminals were successfully identified). But thereafter, emigration had severe repercussions: rather than alleviating pressure on the regime, it created even greater demand for emigration — and thus more criminal activity.

A final piece of evidence comes from detailed data on petitions. The GDR encouraged citizens to communicate a range of demands and grievances to state officials, including the desire to emigrate. Lueders shows that in 1984, over 16,000 petitions were written specifically about emigration, which constituted nearly 28% of the total number of exit visa applications. And these petitions for exit visas increased substantially more in areas with above-average emigration during the initial emigration wave, suggesting that greater emigration in one period was associated with greater demand for it in subsequent periods. An understanding of East Germany illustrates how autocrats face a delicate balance between permitting migration and managing its consequences.

*Research-in-Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4.5-minute read]