Do Incentives Matter When Politics Drive Emigration?

On January 15, 2026, Emil Kamalov, CDDRL’s 2025-26 Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum (SURF) Postdoctoral Fellow, presented his team’s research on whether autocracies can draw citizens who have emigrated back to their country of origin. Historically, episodes of autocratization create huge migration waves. In recent times, countries such as Chile, Venezuela, Iran, Belarus, and Russia have experienced waves of emigration as a result of authoritarian leadership. When skilled professionals who are crucial to their country’s functioning leave, a phenomenon known as “brain drain,” a central question arises: if and how these individuals will return. This raises two key questions: can autocracies reverse such a brain drain and bring their citizens back, or can only democracies do so?

Kamalov turns to the case of Russian migration to explore these questions more directly. For many Russians, the 2022 war with Ukraine was an initial trigger for leaving the country. Kamalov explains that autocrats use emigration as a safety valve to manage dissent at home. In doing so, autocrats rely on several tools to maintain control. These include selective “valving,” which allows some citizens to emigrate while retaining enough workers critical to industry, as well as imprisonment to punish those who attempt to leave. For those who have already emigrated, autocrats may introduce special policies, such as financial or tax benefits for critical professions, in an attempt to attract them back to the country.

Kamalov then discussed what motivates citizens to move into and out of countries. He outlines a list of push and pull factors, including economic conditions, integration and discrimination, and satisfaction with amenities and services. He identifies a gap in the literature, noting that there is relatively little focus on politics — specifically regime change, autocracy, and democracy. From this gap, Kamalov poses several questions: can autocrats lure emigrants back with incentives, will people return if democratization occurs, and does democratic backsliding in host countries push emigrants back home? For political emigrants in particular, political liberties are non-tradable in their decisions about return.

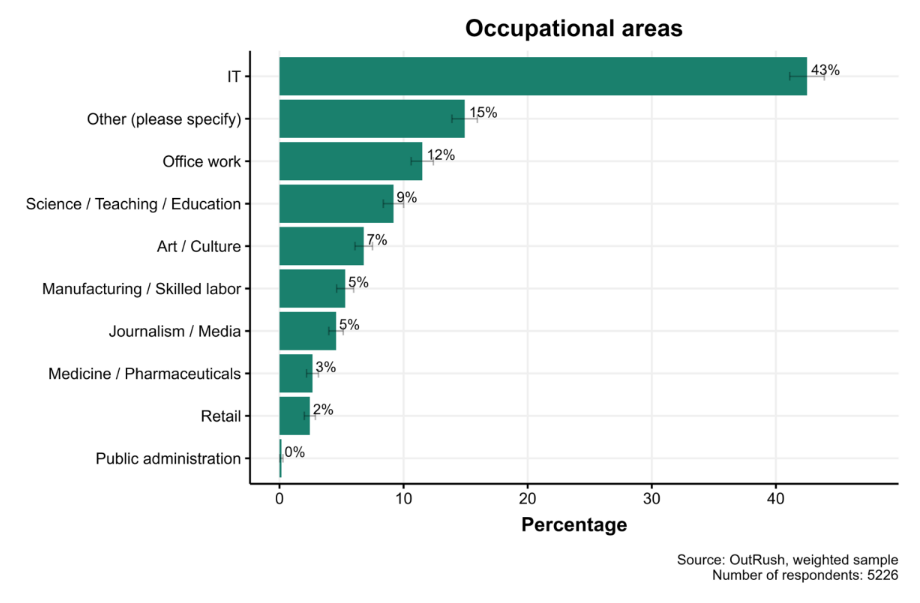

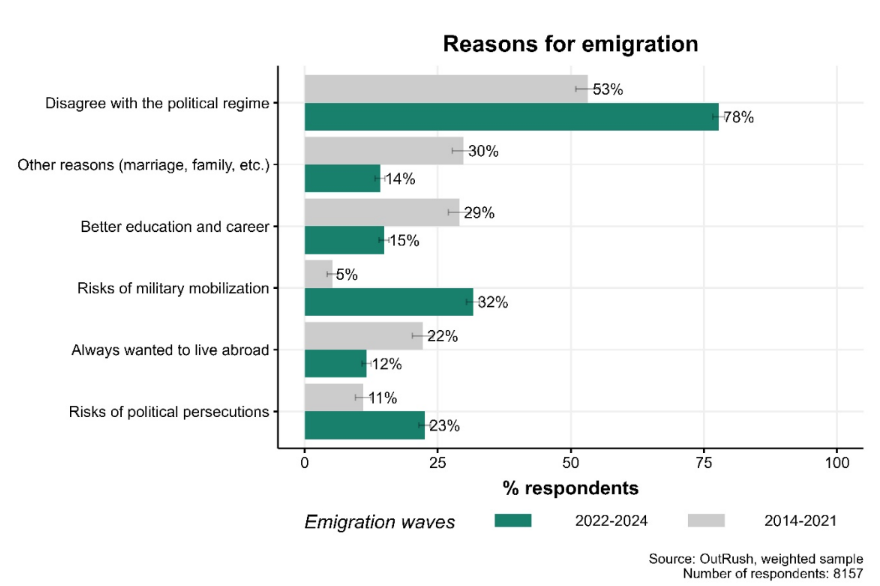

Turning fully to the case of Russian emigration, Kamalov notes that about one million Russians have left the country since the February 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine. This represents the largest brain drain since the collapse of the USSR. Forty-one percent work in the IT sector, and the majority of emigrants are highly skilled and educated, with many working in science, media, and the arts. This emigration represents a significant share of opposition-minded Russian citizens: most of those who left had experience with protest and civic engagement in Russia, and roughly 80 percent cite political reasons for their departure. In response, the Kremlin introduced several policies aimed at discouraging professional emigration or attracting emigrants back. These include mobilization exemptions for highly skilled workers in critical industries such as math, architecture, and engineering, as well as economic support for IT workers, including subsidized mortgages. Because of these policies, Russia serves as a useful case study for understanding whether the strategies autocracies use to entice citizens back or prevent them from leaving are actually effective.

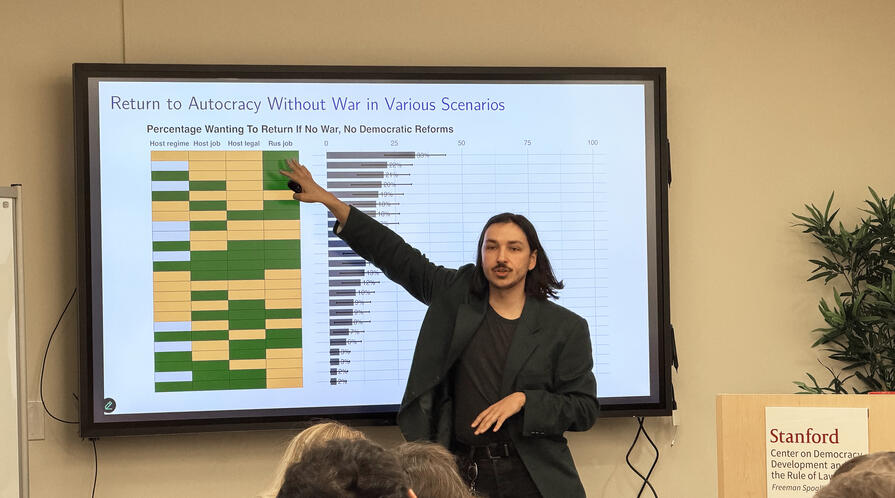

In March 2022, Kamalov and his team launched a panel survey of Russian migrants consisting of five waves. Approximately 21,000 post-2022 Russian emigrants across around 100 countries participated. As part of the survey, respondents were asked to imagine hypothetical political scenarios in Russia and indicate whether they would return if those scenarios became reality. These scenarios ranged from highly realistic but undesirable to unrealistic but highly desirable. They included continued war with Putin in power, continued war with family mobilization exemptions, an end to the war without regime change, an end to the war with political amnesty but no regime change, and full regime change with pro-democratic forces coming to power. The team also analyzed respondents’ host countries, focusing on economic conditions, citizenship opportunities, and political environments.

The results show that having a good job or a path to citizenship in the host country reduces the likelihood of returning to Russia, while democratic backsliding in the host country increases it. Draft exemptions do not increase return at all. Ending the war alone would attract only about 5 percent of emigrants, ending the war combined with political amnesty would attract about 15 percent, while democratization is by far the most attractive scenario, drawing around 40 percent back. When looking at subgroups, all professional categories studied — culture, IT, media, science, and education — were similarly unlikely to return under non-democratic conditions. During democratization, around half would return, though those working in culture, such as artists and musicians, were somewhat less likely to do so. Younger emigrants were more likely to return than older ones.

When asked why they would not return, respondents cited high migration costs, regime volatility, and distrust of Russian society. Some believed that even with political change, Russian society would take much longer to become progressive. Those who said they would return pointed to home, family, opportunities, quality of life, migration fatigue, and, in some cases, disillusionment with democracy in host countries.

The findings of Kamalov’s team demonstrate that even removing the initial trigger for emigration cannot attract many emigrants back. Job opportunities can draw certain subgroups, even during wartime, but broader political conditions matter far more. Autocratic spillovers and cooperation also matter, as democratic backsliding in host countries can motivate return. Importantly, even those who currently cannot envision retu

Read More

SURF postdoctoral fellow Emil Kamalov explains why political freedoms outweigh material benefits for many Russian emigrants considering return.

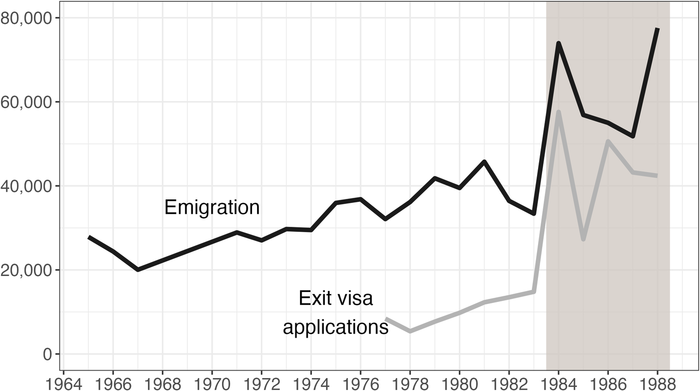

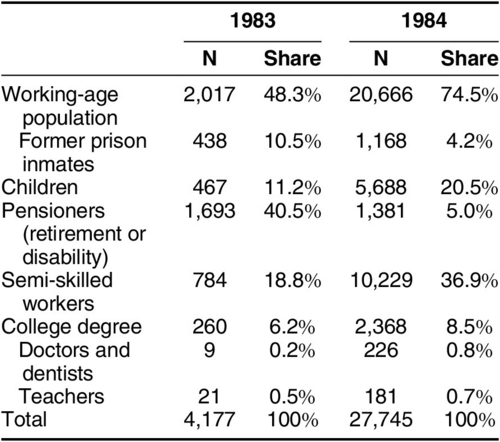

Figure 12. Professional composition of Russian emigration

Figure 12. Professional composition of Russian emigration

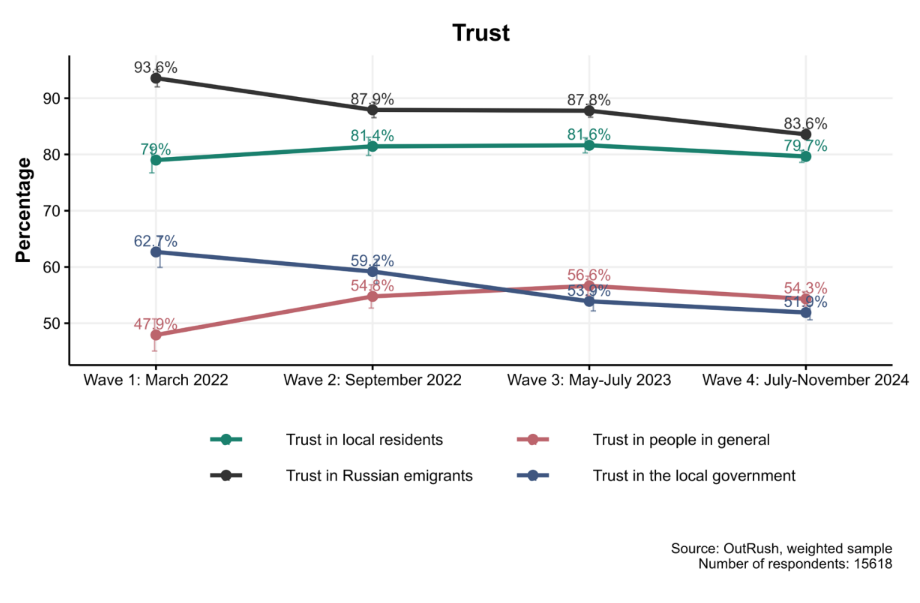

Figure 18. Changes in trust levels

Figure 18. Changes in trust levels

Figure 7. Key reasons for emigration. The question allowed for multiple selections if respondents had difficulty choosing one main reason.

Figure 7. Key reasons for emigration. The question allowed for multiple selections if respondents had difficulty choosing one main reason.