Contracts, Incentives, and Cultural Difference in the Labor Market

Contracts, Incentives, and Cultural Difference in the Labor Market

CDDRL Research-in-Brief [4.5-minute read]

Introduction & Contribution:

Employment contracts vary widely, not only in terms of salary and wage levels but also in rewards (punishments) for good (bad) performance and in the discretion exercised by employers. As employment continues to globalize and transform — for example, with rising levels of gig work or feelings of burnout — our knowledge is partial about the kinds of contracts employers are willing to propose, and the levels of effort employees are willing to exert. In particular, it is not clear that incentives — whether positive or negative — actually encourage significantly more effort from employees; it might be that a non-negligible proportion of workers are intrinsically dedicated to their jobs or intrinsically unmotivated. Meanwhile, it is not clear whether similar contracting scenarios will elicit similar behaviors among employers and employees from different parts of the world.

In “Material incentives and effort choice,” Elwyn Davies and Marcel Fafchamps conduct a series of experimental online games with participants from India, the United States, and five African countries. The experimental component involves randomizing which kinds of contracts the employer players can offer to employee players. After employers propose a contract, employees then choose a level of effort to exert in response. The different interactions between players shed light on how incentives may (or may not) motivate workers and how these motivations differ across cultures.

The authors find a lot of commonality across regions: the majority of participants do not respond to incentives or wage levels when choosing their effort level; a sizable fraction of participants increase effort in response to a higher wage, even in the absence of incentives. The proportion of participants who choose high effort only when incentivized is small in all regions.

The authors also find some stark differences across regions. For example, employee players from India and Africa were more intrinsically motivated, so performance-based incentives were less relevant to them than to American players. Not only were American employees more self-interested, but American employers were more prone to renege on providing bonuses to employees. The authors do not find evidence of cross-country stereotyping or prejudice, meaning that players did not form biased expectations or provide less effort when paired with players from other countries.

“Material incentives and effort choice” greatly deepens our understanding of the (in)effectiveness of incentives. At the same time, the authors take an important step by extending this research program into the Global South, where employer-employee relations are less often studied and where different norms around work may operate. By providing evidence about how people from different countries negotiate and think about effort, the authors draw our attention to important connections between culture and the economy.

Recruitment, Game Rules, and Archetypes:

Participants in the experiments hailed from India, the US, South Africa, Senegal, Kenya, Malawi, and Morocco. They were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk, a digital labor platform, and Facebook advertisements. Participants play four games as employers and four as employees, never against the same person, and most of the time against players from their home country. The experiment takes 15 minutes and does not involve any real effort from employees. Before playing the game, participants were asked questions regarding their beliefs about the effectiveness of incentives and the acceptability of different kinds of rewards and punishments.

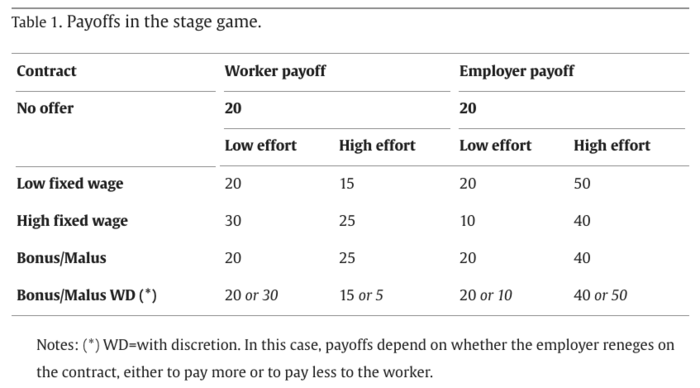

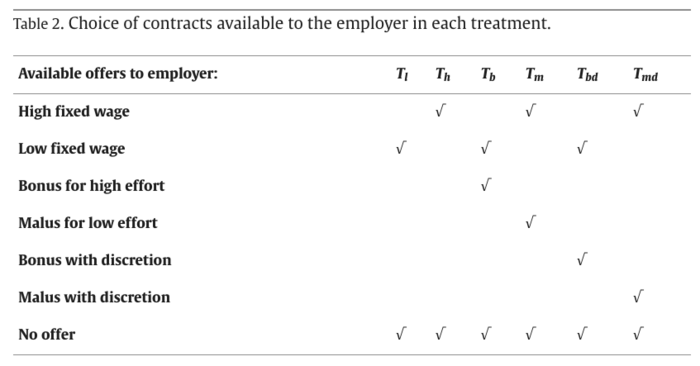

The games begin with employers making a non-negotiable contract offer. Contracts can take one of six forms: a fixed contract with (1) low wages or (2) high wages; those with (3) a bonus for high effort or (4) malus for low effort; finally, contracts (5) and (6) are the same as (3) and (4) but with an employer option to renege on the bonus or malus, respectively. Players attempt to maximize their points. These are calculated based on wage rates and effort levels, which affect the value of what is produced for employers. The games differ in terms of which offers an employer can make — these options, between one and three in total (including making no offer), are randomly selected. The game begins with an employer either making an offer or making no offer; in the latter case, the game ends. Workers then choose a level of effort, in which case the game ends, except for in contracts (5) and (6), where employers choose whether or not to renege.

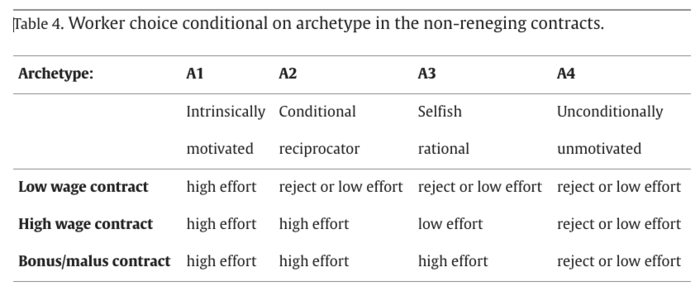

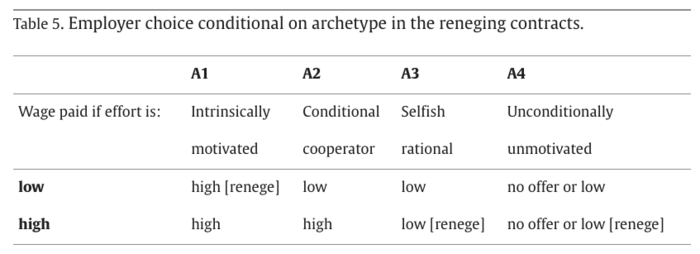

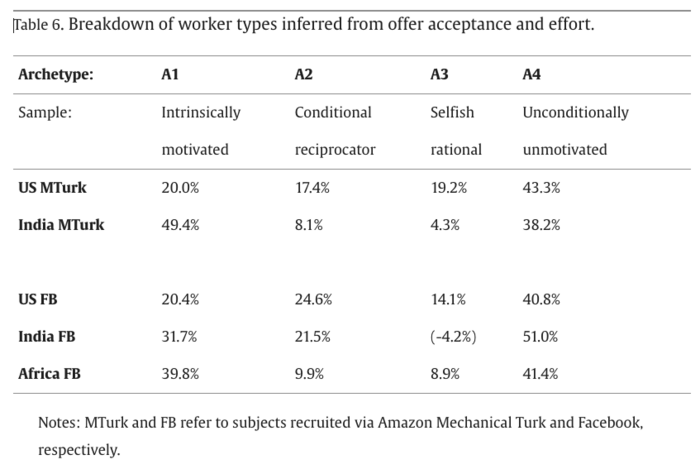

The authors introduce four behavioral “archetypes” to guide their expectations about which kinds of offers will be proposed and accepted, whether employees will exert effort, and whether employers will renege. The first type, Archetype 1, always provides high effort. A2s provide effort only if they are paid a high fixed wage. A3s provide effort only if their contract includes performance incentives. And A4s never provide effort. Of course, a “rational,” benefits-maximizing employee will always exert low effort under contracts (1-2) and high effort for (3-4), while rational employers will always renege on contract (5). To what extent, then, are different archetypes and behaviors borne out in actual interactions?

Findings:

To give just a snapshot of the authors’ many findings, most employers offered contracts rather than ending the games. American employers reneged more often than Indian or African ones. And when employers could renege, employee effort declined sharply. Despite this, employee effort levels remained higher than expected if all employers were selfish, suggesting that workers anticipated some fair or altruistic behavior.

Employee effort varied significantly by contract type and region, as mentioned above. Data from the Amazon Mechanical Turk sample shows that American employees were much less likely to embody the A1 archetype than Indians and much more likely to embody As2-4. Across all samples, roughly one-third to one-half of workers never exerted effort (A4), which poses a dilemma for assumptions about the effectiveness of incentives. The authors find sizable proportions of each archetype on all three continents. Most common are archetypes A1, then A4, A2, and A3. This is an important descriptive finding, as material incentives are clearly not the most significant motivators.

Another set of findings relates to the concepts of stereotyping, defined as employers expecting workers from different countries to work more or less than their co-nationals, and prejudice, whereby employees exert low effort when matched with employers from different countries. The authors found virtually no evidence of stereotyping and no evidence of prejudice behind their results.

In the final part of the paper, the authors investigate whether differences in behavior across regions can be predicted from differences in observable characteristics. They find strong evidence that they cannot. This leaves open the possibility that behavioral differences across regions reflect cultural differences.

Ultimately, “Material incentives and effort choice” underscores the need to rethink our assumptions about workplace motivation, which will be key for designing effective contracts in the evolving global labor market.

*Brief prepared by Adam Fefer.